Commentary

By Katerina Portela | Edited by Lisa Duncan

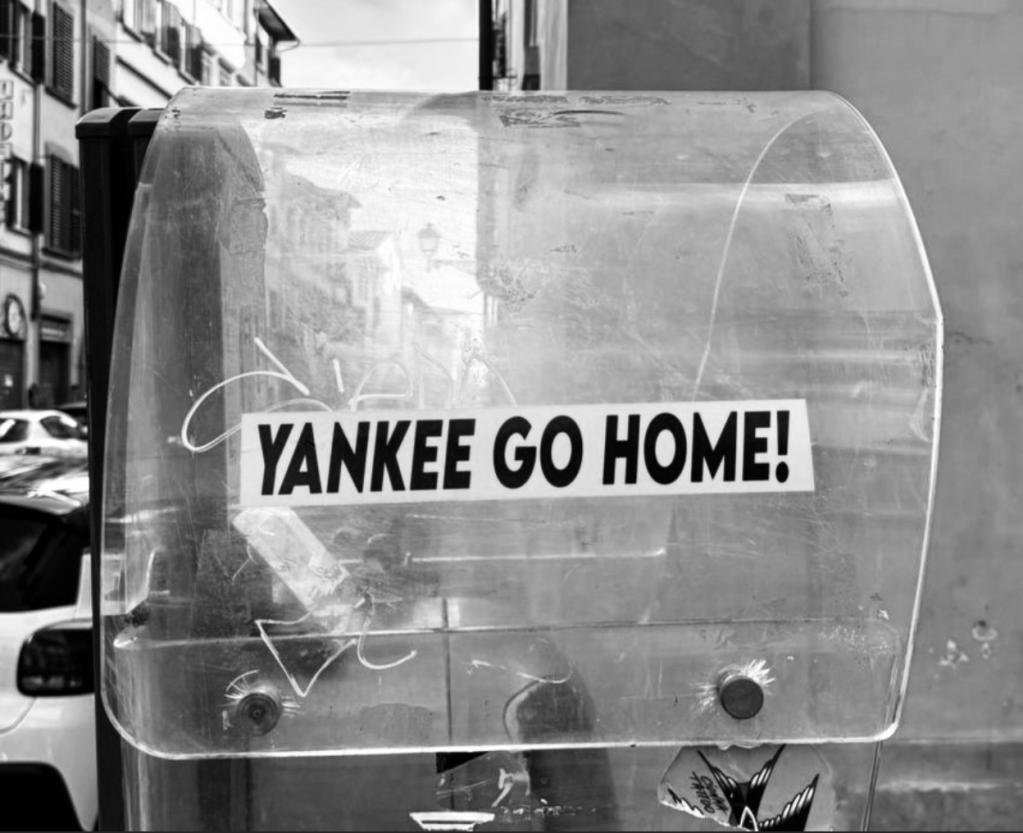

Walking in Florence, visitors may notice a pattern across the city: eye-catching yellow stickers with bold black font that read, “YANKEE GO HOME!” The stickers were plastered all over Florence in late September, whether on street signs or telephone booths. With only three words, the stickers send a strong statement to tourists walking the city—Americans are not welcomed with open arms.

Across Italy, you may see graffiti with similar messages and complaints about Americans. Americans have received a reputation in some places of the world for being loud, self-centered, ignorant, and plain annoying. But where does this perception come from?

Tourism in general creates congestion, gentrification, pollution, and price increases. Americans are actually not the most common group of visitors to Italy overall; Germany and France outrank in this regard.

However, in Rome and Florence specifically, visitors from the United States had the highest number of arrivals in local hotels. In 2023, “arrivals from the U.S. in hotel establishments in (Rome) reached nearly 1.5 million, exceeding pre-pandemic levels,” according to Statista. In Florence, American arrivals this year reached nearly 900,000, a new record.

Angelo Brandelli Costa is an associate professor of psychology at JCU specializing in social and health psychology. Brandelli Costa is also a contributor to a number of academic journals in his field and is editor-in-chief of Trends in Psychology.

Brandelli Costa states that the negative impact of tourism on popular cities leads to general ill will towards the traveling majority.

“In European cities, we are facing an overtourism situation that is increasing the price of rents and is changing the city landscape. If prices go up, people accustomed to living in these places need to move,” said Brandelli Costa. “Of course, if the majority of tourists were coming from China for example, and you end up being Chinese doing something differently in these cities, you’ll be the target of animosity.”

He also connects the animosity to a psychology theory known as social identity theory, which revolves around people seeing themselves differently based on the group they belong to, known as their “in-group.”

“In Europe, people really have strong identities regarding their group of origin, mainly nationality or religion or culture in general. When you create that in-group, automatically, all other groups that are different from you are going to be targeted. You’re going to perceive the differences with them. If you go somewhere like the United States or Brazil, those countries are constructed by immigrants, so the boundaries of in-groups are loose,” Brandelli Costa said.

This theory could explain why locals of Rome and Florence might sharply perceive differences in Americans, as they stick out as part of an ‘out-group’ or a significantly culturally different group.

He adds that in places like America, Canada, and Brazil, one is considered a part of that country from receiving citizenship or living there long enough. In Italy, on the other hand, this is perceived by blood bounds, so the boundary of who is considered ‘in’ is much more exclusive.

James Teasdale is a lecturer in sociology and English at John Cabot University. At the University of Oxford, he researched the concepts of ‘otherness’, migrant attitudes, and race and gender in Britain and other parts of the world. He says that the perceptions might come from general attitudes towards the United States.

“One consistent issue is that people often think, when meeting somebody else, that they are responsible for the culture, political decisions (and) wars of that society and must act as a spokesperson,” Teasdale said.

America’s global influence, positive and negative, sparks changing attitudes and questions about American ways of life, according to Teasdale. Controversial topics like presidents or healthcare might affect how people view Americans in general. With U.S. healthcare largely expensive and inaccessible and presidential elections causing strife, these perceptions lean to the negative.

This division is emphasized by a Pew Research study from last year that found that Americans see the United States as more tolerant and considerate of foreign issues than those in other countries do.

Teasdale adds that topics that are normal to discuss openly in the U.S. may come off differently in Italy.

“Italians, and a lot of Europeans in general, don’t associate so strongly with the ‘American Dream’,” he said. “A lot of North Americans speak very openly and frankly about money, ‘success’, and often this is before a name or handshake has been exchanged. This attitude sometimes rubs people the wrong way, especially if their goals in life don’t necessarily align with this attitude.”

As Brandelli Costa said, tourism, which Americans make up the most of in Rome, can often be a harmful business that can lead to exploitation of resources and space. This could be considered the case in Rome, where the oversaturation of Airbnb is driving Italians away from the center of the city.

“No individual tourist ever sees themself as a problem. Some even try to justify their legitimacy or claim to a place. Regardless of this, their lack of any real social capital, but massive wealth capital, ironically bends the area towards them,” Teasdale said.

Between negative effects from tourism, social identity theory, global attitudes and cultural differences, there are a lot of reasons Americans get put in a negative light in Italy. While there’s no one cause, Americans who want to avoid becoming an “annoying American” may want to be aware of these perceptions and research ways to practice ethical tourism and living.