Commentary

By Miguel Presencio Ortiz | Edited by Jenna Caruso

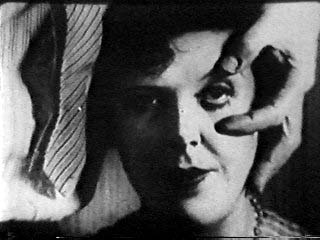

In 1929, The Spanish artists and directors Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali had two dreams that inspired one of the most iconic films in cinema history, Un Chien Andalou. Buñuel had a dream in which a cloud sliced the moon in half “like a razor blade slicing through an eye” and shared it with the artist Salvador Dali, who had a dream in which ants were coming out from his hand.

Fascinated by the capacity of the mind to create symbolic images, they decided to take inspiration from these dreams to create Un Chien Andalou, a silent film considered one of the most influential works of surrealist cinema.

The surrealism movement was born in the 1920s and its mission was to defy the predominant rationalism in European culture and explore the mind through art. As part of this movement, Dalí and Buñuel aimed to challenge established values and navigate the unconscious with this film. On the other hand, as Un Chien Andalou does not follow a linear plot and presents independent surrealist scenes, it has been interpreted differently on numerous occasions.

Many authors relate this film to Sigmund Freud’s theories about the unconscious and the oedipal desire, due to the sexual symbolism of the film. However, I see this film as the depiction of the pressure men experience to stick to gender roles and the process they have to undergo in order to discover their identity.

The opposition between gender fluidity and repression is reflected numerous times throughout the film. We first see the juxtaposition of these forces in one scene in which a policeman stops an androgynous character for poking a severed hand with a stick. This prohibition makes the character paralyzed; unable to dodge a car that ends up running them over. Beneath all the surrealism in this scene, we could interpret the death of the non-binary character as a metaphor for the death of men’s gender fluidity after societal pressure forces them to stick to masculinity canons.

At the same time, the car accident is closely observed from a window by a man that waits impatiently for the androgynous’ death. We could interpret his desire to see the other character’s death as his longing to get rid of the part of himself that he sees reflected in the other character. The androgynous character could be seen as the embodiment of gender fluidity or femininity, so as men are taught to hide this part of themselves, this scene could be a metaphor of how men get rid of their feminine side in order to achieve societal validation.

After the death of the androgynous, the man gets aggressive with a woman that accompanies him, and he sexually harasses her. A possible interpretation for this scene is that after repressing his gender fluidity, the man has replaced it with the toxic masculinity imposed by society. For that reason, he takes a superior role towards the woman and thinks he has the right of taking advantage of her. Finally, she is able to escape him by pushing him, but the man keeps chasing her. He tries to reach her but suddenly two ropes appear, and he takes them to drag everything that is tied to them.

All the objects tied to the rope are symbolic and represent the burden of following societal rules. Among the different things attached to the rope, there are two slabs as a religious reference to the ten commandments and two priests as the personification of the moral values imposed by the church.

The contrast between gender freedom and societal repression is again present in a confrontation between a suited man and a man in female attire. In this scene, the suited man gets furious after seeing what the other character is wearing and forces him to take off his feminine clothes. Then, he makes him face the wall and gives him some books. However, these books transform into a gun that he uses to kill the suited man. This moment seems to represent how society punishes people that stick out and express their gender freely, but education and knowledge can be used as a weapon to fight this oppression.

Just before the suited man is going to be shot, it’s revealed that both characters were the same person. This could be a depiction of how men internalize societal values so much that they become their own force of repression. However, using what the knowledge they have acquired from education, they are able to face the part of themselves that prevents them from being free.

All in all, Un Chien Andalou could be seen as the representation of the journey men undertake to embrace the feminine side that they have been taught to hide. This process implies revising the values they have internalized and facing the part of themselves that makes them their own force of repression. On the other hand, I interpret this film as a metaphor of the pressure that society and tradition put on men to fit into a masculinity canon and how they could free themselves from it through education and knowledge.

Surely, Dali and Buñuel’s original idea wasn’t to subvert gender roles in this film; however, the surrealist images that compose this work make it open to new interpretations and meanings. For that reason, Un Chien Andalou is a timeless work that still speaks to our present and relates to us, uncovering a problem that many men suffer nowadays.